Author: Cedric Mangeh (RAIN)

Sorghum Sudangrass (SS) tolerates drought better than many other forages and bounces back fast for multiple cuts in a single season. It has become a favorite among Northern Ontario producers. To improve palatability, digestibility and yield, more growers have been pushing for higher seeding rates, without knowing that a quiet issue is creeping in. Crop emergence and performance became weaker the following year. Could allelopathy, a phenomenon where plants release chemical compounds into the ground that may suppress the growth of subsequent crops, be the reason?

Important note: Our team is still evaluating any carry-over impacts. We are sharing early findings, not final recommendations.

What does this mean for Northern Ontario SS Growers:

Like SS, forage crops play a crucial role in ensuring that Northern Ontario farms remain productive and sustainable. But growing good forage is getting harder due to shorter growing seasons, erratic rainfall, while rising costs are tightening the margins. This project is about finding the right balance, “The Sweet Spot”. So, how can producers boost yield, forage quality, and digestibility with smart seeding rates, without compromising next year’s crops?

Key Findings from the Field:

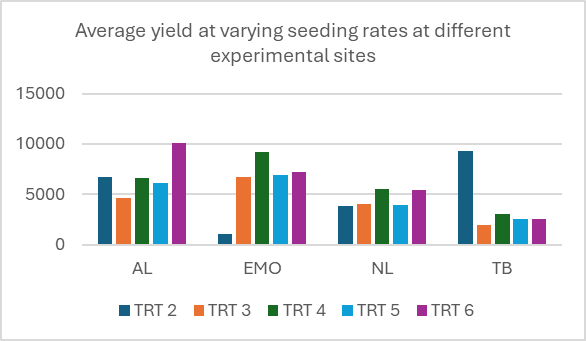

Here’s what we learned from trials across Northern Ontario (Algoma (on-farm), Thunder Bay, Emo, and New Liskeard):

Promising Seeding Rates: Yield

The optimal seeding rate for SSSR was found to be between 62.5 and 80.3 lbs/ac, as confirmed by yield data across all sites. Although the effect of seeding rates alone was not statistically significant due to insufficient data size, the interaction between site local conditions and seeding rate had the most significant impact on the average yield of SS.

- In Algoma, the average top yield, 9031.67lbs/ac, was obtained at SS90 (80.3 lbs./ac)

- In Emo, Thunder Bay, & New Liskeard the best average yields (8165.67 lbs./ac 7828.87 lbs./ac, and 2704.19 lbs./ac respectively) were obtained at SS70 (62.5 lbs./ac)

An optimal stand of Sorghum-Sudangrass, seeded at 62.5–80.3 lbs./ac, balances plant density to maximize yield and forage quality, with better digestibility and lower fiber content. In contrast, a dense stand (seeding rate > 89.2 lbs./ac) leads to overcrowding, thinner stems, reduced quality (higher ADF/NDF), and increased risk of lodging, despite slightly higher biomass.

Promising Seeding Rates: Forage Quality

Crude Protein

Changes in seeding rates between 62.5–80.3 lbs./ac showed medium to high variability (11.95 % ≤ C.V. ≤ 31.78 %) indicating that different SSSR moderately to strongly influence CP.

- In NL, AL, and Emo the highest CP levels were attained at SS80, SS90, and SS70 (10.56%, 10.13%, and 8.69%) respectively

- In TB, the highest CP was obtained at SS45 (15.40%) closely followed by SS90 (12.68%)

While the effects of seeding rate on CP were not statistically significant due to insufficient data size, an interaction between the different treatments and site local conditions had strongest effects on CP levels in SS consistently across all sites.

Digestibility and fiber

Digestibility and fiber stayed mostly the same across different seeding rates at different sites. This practically implies that it is possible to boost protein without sacrificing digestibility. Although digestibility, fibers, and net energies did not respond to variations in seeding rate, they were strongly influenced by site conditions and harvest maturity. Therefore, managing harvest timing to meet specific nutritional targets for dairy or beef operations are of critical importance. For dairy producers, earlier harvesting, preferably between the boot and soft dough stages, can help maximize net energy concentrations, improving milk production potential. On the other hand, delaying too far (hard dough to physiological maturity) can compromise feed quality, reducing overall animal performance, although slightly later harvests (between soft dough and hard dough) might be acceptable.

Nutrient Uptake

Across all experimental sites, SS showed varying nutrient uptake patterns influenced by seeding rates, soil conditions, and harvest timing. Nutrient levels in the plants were highest when seeding rates were in the 62.5–80.3 lbs./ac range. Practically, therefore, to get the most from your crop, match seeding rates with soil management best practices.

- In Algoma, cooler temperatures and low soil fertility limited overall uptake, but lower seeding rates (SS45) unexpectedly performed best for several nutrients

- In contrast, EMO’s late harvest and drainage issues meant that seeding rates had little impact, though nutrient peaks varied by rate

- New Liskeard saw optimal uptake of macro- and micronutrients at 62.5–80.3 lbs./ac, though its alkaline soils reduced Fe and Mn availability, suggesting foliar supplementation may be needed

- Thunder Bay experienced the most variation, with SS90 (80.3 lbs./ac) emerging as the best rate for maximizing nutrient uptake, especially for potassium

Harvest Timing Matters

Cutting between the Flag Leaf Visible Stage and Soft Dough yielded the best digestibility and energy content. Don’t wait too long because earlier harvests can improve feed quality.

What’s Next: There is More to Learn from These Fields:

While these early findings are promising, they’re just the beginning. The next phase of the research will investigate what happens after Sorghum-Sudangrass comes off the field. In the coming season, alfalfa and canola will be planted on these same plots previously occupied by Sorghum Sudangrass, barley and corn. The goal is to:

- Evaluate how previous sorghum crops influence new plantings

- Determine whether allelopathy contributes to reducing second-year yields. It can be a concern when crops like Sorghum Sudangrass leave behind natural compounds (with higher seeding rates, more of such compounds are released) that may suppress emergence and early growth of small-seeded crops like alfalfa or canola

- Identify management practices that can mitigate those effects

So, while optimized seeding rates are already showing benefits, the full story, including solid recommendations, is still unfolding. We’ll continue sharing what works, what to monitor, and how it all fits into your crop planning decisions.

Wrap-up:

This research is being performed in real farms across Northern Ontario, with challenges you know firsthand; shorter growing seasons, soils fertility, and the pressure to make every acre count. Sorghum-Sudangrass shows strong potential when seeded at the right rate, especially in the 62.5–80.3 lbs/ac range. But we’re not stopping there. The next season will show us what comes after, the long-term impact on follow-up crops like alfalfa and canola. That’s when real recommendations start to take shape. If you’re thinking about trying Sorghum-Sudangrass, adjusting your seeding rate, or planning next year’s rotation, or want trial results as soon as they’re out? Sign up to our email newsletter at www.rainalgoma.ca/contact

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by funding from the Sustainable Canadian Agricultural Partnership program (Sustainable CAP) and the Northern Ontario Heritage Fund Corporation (NOHFC). This project is delivered in partnership with Dr. Tarlok Sahota (Lakehead University Agriculture Research Station), the Ontario Crops Research Centre – New Liskeard/Emo, the Northern Ontario Farm Innovation Alliance (NOFIA), and David Thompson (RAIN). Everyone’s contributions make this work possible across multiple farm sites in Northern Ontario.